In this lesson, we’ll finish drawing the tic marks and labels on our Cartesian plane graphic. We’ll also have another look at encapsulation, specifically in the context of line positioning and drawing. Our strategy for labeling the major tic marks will require us to discuss the Iterator and Iterable interfaces, and we’ll also have a look at inner classes. We’ll start with a discussion of the Iterator and Iterable interfaces.

GitHub repository: Cartesian Plane Part 4

Previous lesson: Cartesian Plane Lesson 3

Interfaces

Let’s have a quick review of interfaces. An interface is a type, much like a class. Interfaces contain descriptions of methods without the method implementations (traditionally, interfaces contain no implementation code at all; this is no longer true, but let’s leave that discussion for another time). A class can implement one or more interfaces; if a class implements an interface, it is required to implement the methods described by the interface (or declare itself abstract, which can defer method implementation to concrete subclasses). One of the most commonly implemented interfaces is the Runnable interface. If you look at the documentation for Runnable, you will see that it describes the run method as follows:

void run()The Root class that we have been using in our lessons is an example of a class that implements Runnable; in summary, it looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | public class Root implements Runnable { // ... /** * Required by the Runnable interface. * This method is the place where the initial content * of the frame must be configured. */ public void run() { /* Instantiate the frame. */ frame = new JFrame( "Graphics Frame" ); // ... } // ... } |

Interfaces can be parameterized. Parameterized interfaces can be tailored to work with a specific type. One of the most popular such interfaces is List<E>. A List<E> is declared like this:

interface List<E> { ... }It describes methods declared this way:

void add(int index, E element);

E get(int index)When you declare a variable of type List, you substitute a type for the E; you’ve probably already done something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | public class ListDemo { public static void main( String[] args ) { List<String> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add( "string 1" ); list.add( "string 2" ); String str = list.get( 1 ); System.out.println( str ); } } |

In your code, the type you declare inside the diamond operator (<String>) is substituted for E, and now any operations on your list are limited to use with Strings.

Parameterization can be an involved topic but, for the moment, we’ve covered all we need to know. To learn more about interfaces, see the Oracle tutorial Interfaces and Inheritance. For more about parameterization, see the Oracle Tutorial Generics.

A bit more about Parameterization (also referred to as Generics):

You cannot parameterize on a primitive type, only on a class or an interface. You cannot have a List of ints or booleans. Recall, however, that every primitive type has a corresponding wrapper class, so you can have a List of type Integer or Boolean. This may be confusing if you’ve ever seen code that looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | public class AutoboxingDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Integer> iList = new ArrayList<>(); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 10 ; ++inx ) iList.add( inx ); iList.set( 5, 42 ); } } |

To clear up the confusion, the code at lines 7 and 8 does not add primitive values to iList; instead, the compiler automatically converts the int primitive to an instance of its wrapper class, Integer, in an operation called autoboxing. The above code is equivalent to this:

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 10 ; ++inx )

iList.add( Integer.valueOf( inx ) );

iList.set( 5, Integer.valueOf( 42 ) );

Iterators and Iterables

In Java, an iterator is something that produces a sequence of values. The interface Iterator<E> describes a type that produces a sequence of values of type E. If you look at the documentation for Interface Iterator<E>, you’ll see that implementing it requires you to write two methods:

boolean hasNext()

E next()The method next() returns the next value in the sequence (assuming there is one). The method hasNext() returns true if the iterator has a next element to return. If hasNext() is false, calling next() precipitates a NoSuchElementException. A common example of an iterator is ListIterator<E>. If you have a variable of type List<String>, invoking method listIterator() returns an object of type ListIterator<String> that can be used to traverse the contents of the list. Here’s an example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | public class listIteratorDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add( "every" ); list.add( "good" ); list.add( "boy" ); list.add( "deserves" ); list.add( "favor" ); ListIterator<String> iter = list.listIterator(); while ( iter.hasNext() ) { String str = iter.next(); System.out.println( str ); } } } |

Writing your own iterator isn’t difficult. You need an object that stores enough state to know the first and next elements to produce and when the sequence has been exhausted. Let’s write the class IntIterator, which implements Iterator<Integer> and iterates over a range of integers. We’ll have a constructor describing the target range and instance variables describing the next integer to produce and the range’s upper bound.

private final int upperBound;

private int next;

public IntIterator( int lowerBound, int upperBound )

{

this.upperBound = upperBound;

next = lowerBound;

}

Note: You may ask, “Why did you make upperBound final”? The answer is because I could. Declaring variables to be final (meaning they can’t be changed after initialization) makes your code more reliable and easier to maintain. It’s a good habit to make your fields final whenever you can.

Now we need a hasNext() method that compares next to upperBound, and a next() method that correctly manipulates the value of next. Here’s the complete class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 | public class IntIterator implements Iterator<Integer> { private final int upperBound; private int next; // Iterates over the sequence num, //where lowerBound <= num < upperBound public IntIterator( int lowerBound, int upperBound ) { this.upperBound = upperBound; next = lowerBound; } @Override public boolean hasNext() { boolean hasNext = next < upperBound; return hasNext; } /** * Returns the next element in the range. * * Bloch Item 74 * "Use the Javadoc @throws tag to document each exception * that a method can throw, but do not use the throws keyword * on unchecked exceptions." * (Bloch, Joshua. Effective Java (p. 304). Pearson Education. Kindle Edition.) * * @throws NoSuchElementException if the bounds * of the iterator are exceeded */ @Override public Integer next() { if ( next >= upperBound ) throw new NoSuchElementException( "iterator exhausted" ); int nextInt = next++; return nextInt; } } |

A class that implements Iterable<E> simply has a method named iterator() that returns an object of type Iterator<E>. The List<E> interface has such a method (allowing us to say that a List<E> is iterable). The nice thing about iterable objects is that they can be used in an enhanced for statement (a.k.a. for-each loop). Here’s an example:

Note: For more about the enhanced for statement, see The for Statement in the Oracle Java tutorial.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | public class ForEachDemo { public static void main( String[] args ) { List<String> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add( "every" ); list.add( "good" ); list.add( "boy" ); list.add( "deserves" ); list.add( "favor" ); for ( String str : list ) System.out.println( str ); } } |

If we want a class that produces objects that can iterate over a range of integers inum1 through inumN, all we need to do is implement the method Iterator<Integer> iterator() that returns new IntIterator(inum1, inumN). Let’s write such a class:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 | public class Range implements Iterable<Integer> { private final int lowerBound; private final int upperBound; // Iterable over num, // where lowerBound <= num < upperBound public Range( int lowerBound, int upperBound ) { this.lowerBound = lowerBound; this.upperBound = upperBound; } public Iterator<Integer> iterator() { IntIterator iter = new IntIterator( upperBound, lowerBound ); return iter; } } |

And here’s an example that uses our Range class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | public class RangeDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { Range range = new Range( -10, 10 ); for ( int num : range ) System.out.println( num ); } } |

A quick look at inner classes

Another strategy for creating iterable classes is to declare the iterator class directly inside the class that uses it. A class declared directly inside another class is called a nested class. The class may be declared static; if it is not static, it is an inner class. The advantage of inner classes is that they have access to all the instance variables and instance methods inside the class that contains them (the outer class). Here’s a trivial example.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 | public class InnerClassDemo { private double datum; private DatumRoot fourthRoot; public static void main( String[] args ) { InnerClassDemo demo = new InnerClassDemo( 16 ); System.out.println( demo.fourthRoot.getRoot() ); } public InnerClassDemo( double datum ) { this.datum = datum; fourthRoot = new DatumRoot( 4 ); } private void printMessage( String msg ) { System.out.println( "Message: " + msg ); } private class DatumRoot { private double radicand; private DatumRoot( double radicand ) { this.radicand = radicand; } private double getRoot() { printMessage( "calculating root" ); double root = Math.pow( datum, 1 / radicand ); return root; } } } |

The above code serves no purpose other than to demonstrate that an instance of the inner class (DatumRoot) can access the instance variable (datum) and instance method (printMessage) of the outer class (InnerClassDemo).

We can apply this strategy to the Range class, for example. If we declare the iterator to be an inner class in Range, we have a) a Range class with no external dependencies on other classes and b) a simplified iterator that doesn’t have to store lowerBound and upperBound in its own state; instead, it obtains these values from the outer class. Here is the code for the enhanced Range class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 | public class RangeWithInnerClass implements Iterable<Integer> { private final int lowerBound; private final int upperBound; // Iterable over num, // where lowerBound <= num < upperBound public RangeWithInnerClass( int lowerBound, int upperBound ) { this.lowerBound = lowerBound; this.upperBound = upperBound; } public Iterator<Integer> iterator() { InnerIntIterator iter = new InnerIntIterator(); return iter; } private class InnerIntIterator implements Iterator<Integer> { private int next = lowerBound; @Override public boolean hasNext() { boolean hasNext = next < upperBound; return hasNext; } @Override public Integer next() { if ( next >= upperBound ) throw new NoSuchElementException( "iterator exhausted" ); int nextInt = next++; return nextInt; } } } |

See Nested Classes in the Oracle Java Tutorial for more information about inner classes.

Encapsulating Line Drawing

Our next task is to encapsulate line drawing in our Cartesian plane project. Why encapsulate line drawing? For one thing, it applies to many different pieces of our drawing logic:

- Drawing the grid lines.

- Drawing the axes.

- Drawing the minor tic marks.

- Drawing the major tic marks.

- Even label positioning can benefit from a line-drawing facility; for example, we can generate the positions of the major tic marks on the y-axis and then position the labels to their right.

(Other reasons: it’s a great exercise in encapsulation and writing iterators, iterables, and inner classes.)

The LineGenerator Class

Let’s have a separate class that can describe the coordinates of our grid’s necessary horizontal and vertical lines. It will be type Iterable<Line2D>, capable of iterating through horizontal lines, vertical lines, or both. The following sections will describe the class and instance variables, helper methods, and public methods for our class.

⏹ Class and Instance Variables

The following constant variables tell us which lines to iterate on; the options are horizontal, vertical, and both. Note that the HORIZONTAL value maps to the 1-bit of an integer location, the VERTICAL value maps to the 2-bit, and BOTH is the bitwise or of HORIZONTAL and VERTICAL. To determine if the user wants us to generate horizontal lines, we can ask: if ( (orientation & HORIZONTAL) != 0 )

iterate the horizontal lines

1 2 3 4 5 6 | public class LineGenerator implements Iterable<Line2D> { public static final int HORIZONTAL = 1; public static final int VERTICAL = 2; public static final int BOTH = HORIZONTAL | VERTICAL; // ... |

∎ Instance Variables

For a LineGenerator instance’s state, we’ll need to keep track of various grid properties, including the bounding rectangle, the number of pixels per unit of measure, and the number of lines per unit. We will also need to know the length of a line and the total number of horizontal and vertical lines to draw. Here is an annotated listing of the state variable declarations.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | public class LineGenerator implements Iterable<Line2D> { // ... private final float gpu; private final float lpu; private final float horLength; private final float vertLength; private final int orientation; private final List<Line2D> axes = new LinkedList<>(); private final List<Line2D> horLines = new LinkedList<>(); private final List<Line2D> vertLines = new LinkedList<>(); private final float originXco; private final float originYco; private final float leftLimit; private final float rightLimit; private final float topLimit; private final float bottomLimit; // ... |

- Line 4: This is the grid unit, i.e., pixels-per-unit of measure. It is set in the constructor.

- Line 5: This is the number of lines per unit; it is set in the constructor.

- Lines 6,7: Horizontal and vertical line lengths. For tic marks, these will have the same value. For grid lines and axes, the horizontal length will be the width of the bounding rectangle, and the vertical length will be the height. They are configured in the constructor.

- Line 8: The orientation supplied in the constructor, HORIZONTAL, VERTICAL, or BOTH.

- Lines 10-12: Lists containing the coordinates of the lines to be generated; they are all configured in the constructor. All possible lines are generated each time a LineGenerator is instantiated.

- Line 10: A list containing the coordinates of the axes.

- Line 11: A list containing the coordinates of the horizontal lines.

- Line 12: A list containing the coordinates of the vertical lines.

- Lines 14-19: These variables are declared for the convenience of helper methods. They are derived from the input parameters and set in the constructor.

- Line 14: The x-coordinate of the grid’s origin, equivalent to calling getCenterX() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

- Line 15: The y-coordinate of the grid’s origin, equivalent to calling getCenterY() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

- Line 16: The left-most coordinate of the grid, equivalent to calling getMinX() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

- Line 17: The right-most coordinate of the grid, equivalent to calling getMaxX() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

- Line 18: The top-most coordinate of the grid, equivalent to calling getMinY() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

- Line 19: The bottom-most coordinate of the grid, equivalent to calling getMaxY() on the grid’s bounding rectangle.

⏹ Private Methods

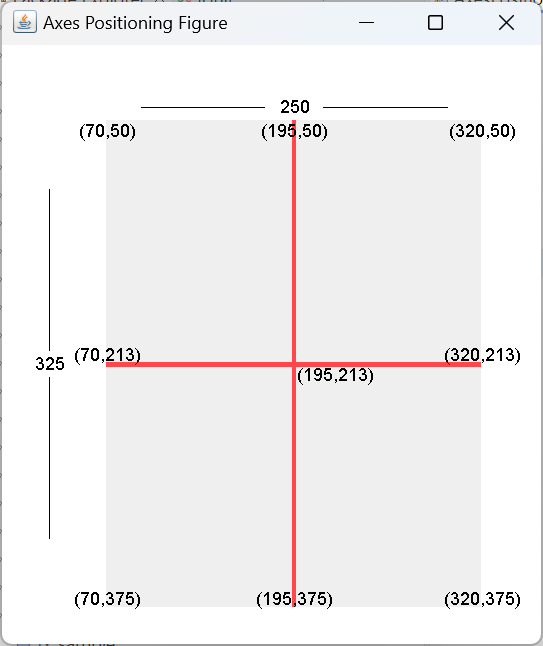

The three private methods for the LineGenerator class are used to compute the grid’s axes (axial lines) and its non-axial lines (the horizontal and vertical lines that are not the x- or y-axis). The x-axis is a horizontal line positioned at the vertical center of the bounding rectangle; the y-axis is the vertical line at the horizontal center of the rectangle. If a bounding rectangle has an upper-left corner of (x=70,y=150), a width of 250, and a height of 325, the coordinates of the x-axis will be:

- x1 = x = 70

- y1 = y + height / 2 = 213

- x2 = x1 + width = 320

- y2 = y1 = 213

and the coordinates of the y-axis will be:

- x1 = x + width / 2 = 195

- y1 = y = 50

- x2 = x1 = 195

- y2 = y1 + height = 375

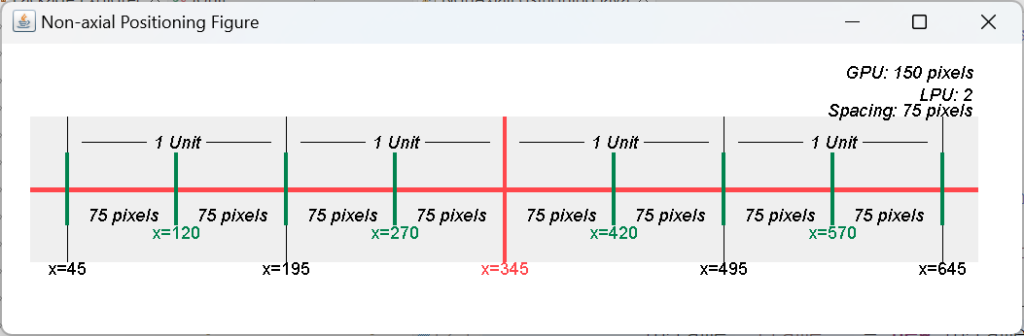

The generated non-axial lines never include the lines x=0 or y=0. The spacing between lines is computed from the quotient of the grid unit (GPU) and the lines per unit (LPU). If the GPU is 100 and the LPU is 2, there will be 50 pixels between lines. The positions of vertical lines are calculated beginning at the x-axis, and the positions of the horizontal lines are calculated starting at the y-axis. So if the x-axis is located at x=345 and the spacing is 75, there will be lines at x=345 – 75, x=345 – 150… and at x=345 + 75, x=345 + 150, etc.

∎ private void computeAxes()

∎ private void computeVerticals()

∎ private void computeHorizontals()

We have three methods to generate lines in the bounding rectangle. The method computeAxes generates the x- and y-axes and stores them in the list referenced by the axes instance variable. It looks like this:

private void computeAxes()

{

Point2D hPoint1 = new Point2D.Double( leftLimit, originYco );

Point2D hPoint2 = new Point2D.Double( rightLimit, originYco );

Point2D vPoint1 = new Point2D.Double( originXco, topLimit );

Point2D vPoint2 = new Point2D.Double( originXco, bottomLimit );

axes.add( new Line2D.Double( hPoint1, hPoint2 ) );

axes.add( new Line2D.Double( vPoint1, vPoint2 ) );

}The computeVerticals method generates the non-axial vertical lines. It starts at the x-axis and generates vertical lines at spacing intervals to the left; then, it returns to the x-axis and repeats the process to the right. The annotated code follows; see also Instance Variables above.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 | private final List<Line2D> vertLines = new LinkedList<>(); // ... private void computeVerticals() { float spacing = gpu / lpu; float yco1 = originYco - vertLength / 2; float yco2 = originYco + vertLength / 2; for ( float xco = originXco - spacing ; xco > leftLimit ; xco -= spacing ) { Point2D top = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco1 ); Point2D bottom = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco2 ); Line2D line = new Line2D.Double( top, bottom ); vertLines.add( 0, line ); } for ( float xco = originXco + spacing ; xco < rightLimit ; xco += spacing ) { Point2D top = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco1 ); Point2D bottom = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco2 ); Line2D line = new Line2D.Double( top, bottom ); vertLines.add( line ); } } |

- Line 1: This is the list for storing vertical lines. We made it a LinkedList instead of an ArrayList because half the elements we add are added at the top of the list (line 18 below), and linked lists are better at storing things at the top or in the middle.

- Line 5: Computes the line spacing.

- Line 6: Computes the y-coordinate of the endpoint of each vertical line above the x-axis.

- Line 7: Computes the y-coordinate of the endpoint of each vertical line below the x-axis.

- Lines 9-20: This for loop generates lines to the left of the x-axis:

- Line 10: Generate the x-coordinate of the first line to the left of the y-axis.

- Line 11: Finish the loop when the x-coordinate arrives at or passes the left edge of the bounding rectangle.

- Line 12: Generate the x-coordinate of the next line to the left.

- Lines 15,16: Compute the top and bottom coordinates of the vertical line.

- Line 17: Generate the vertical line.

- Line 18: Add the line to the top of the list of vertical lines. Note that when the loop finishes, the list will consist of vertical lines in ascending order of their x-coordinates.

- Lines 20-31: Lines 9-20: This for loop to generates lines to the right of the x-axis. Equivalent to the previous for loop, except:

- Lines 22-24: Generates sequential x-coordinates to the right of the y-axis.

- Line 30: Adds the new line to the bottom of the list of vertical lines.

The computeHorizontals method is very similar to computeVerticals. It starts at the x-axis and generates lines above it, adding each line to the top of the horLines linked list. Then, it generates the lines below the x-axis, adding each to the bottom of the horLines linked list. The code is in the GitHub repository.

⏹ Constructors and Public Methods

Our primary constructor will establish the values of all our instance variables and generate all the lines; see also Instance Variables above. Here’s an annotated listing of this constructor.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 | public LineGenerator( Rectangle2D rect, float gridUnit, float lpu, float length, int orientation ) { this.gpu = gridUnit; this.lpu = lpu; this.horLength = length != -1 ? length : (float)rect.getWidth(); this.vertLength = length != -1 ? length : (float)rect.getHeight(); this.orientation = orientation; originXco = (float)rect.getCenterX(); originYco = (float)rect.getCenterY(); leftLimit = (float)rect.getMinX(); rightLimit = (float)rect.getMaxX(); topLimit = (float)rect.getMinY(); bottomLimit = (float)rect.getMaxY(); computeHorizontals(); computeVerticals(); computeAxes(); } |

- Line 2: The bounding rectangle for the grid.

- Line 3: The pixels-per-unit (grid unit).

- Line 4: The lines-per-unit.

- Line 5: The length of a line. If this value is -1, the length will be set at the rectangle’s width for horizontal lines and its height for vertical lines.

- Line 6: The orientation, HORIZONTAL, VERTICAL, or BOTH.

- Lines 9-13: Initialize the state variables for the grid unit, lines-per-unit, length, and orientation.

- Lines 15-20: Initialize the convenience variables described in Instance Variables above.

- Lines 21-23: Build the lists of line coordinates. Note that all the lists are fully configured regardless of the orientation parameter’s value.

Some of our constructors allow the line length and/or orientation to be set to a default for the user’s convenience. As we did with the CartesianPlane constructors, we’ll use chaining for the constructor implementations. Here are our additional constructors.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | public LineGenerator( Rectangle2D rect, float gridUnit, float lpu ) { this( rect, gridUnit, lpu, -1, BOTH ); } public LineGenerator( Rectangle2D rect, float gridUnit, float lpu, float length ) { this( rect, gridUnit, lpu, length, BOTH ); } |

∎ public float getHorLineCount()

∎ public float getVertLineCount()

In addition to the iterator method required by the Iterable interface, we’ll have getters for the vertical and horizontal line counts. (These are primarily for support of the label drawing logic.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | public float getHorLineCount() { return horLines.size(); } public float getVertLineCont() { return vertLines.size(); } |

∎ public Iterator<Line2D> iterator()

∎ public Iterator axesIterator()

The iterator method is required by our class declaration, public class LineGenerator implements Iterable<Line2D>. It takes a straightforward approach to generating an iterator. Depending on the orientation, it creates a list consisting of the vertical and/or horizontal lines and returns the list’s iterator. The axesIterator method will generate an iterator for the x- and y-axes. The methods look like this:

@Override

public Iterator<Line2D> iterator()

{

List<Line2D> allLines = new ArrayList<>();

if ( (orientation & HORIZONTAL) != 0 )

allLines.addAll( horLines );

if ( (orientation & VERTICAL) != 0 )

allLines.addAll( vertLines );

Iterator<Line2D> iter = allLines.iterator();

return iter;

}

public Iterator<Line2D> axesIterator()

{

return axes.iterator();

}∎ public static Iterator axesIterator( Rectangle2D rect )

Finally, for the user’s convenience, we have a class method that returns an iterator for the axes of a given bounding rectangle. As mentioned, we can get an axes iterator from any LineGenerator object. However, in some contexts, this code: Iterator axes = LineGenerator.axesIterator( gridRect );

might appear more logical than this code: LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, gridLineLPU );

Iterator axes = lineGen.axesIterator();

A listing of this method follows.

public static Iterator<Line2D> axesIterator( Rectangle2D rect )

{

LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( rect, 1, 1, -1 );

Iterator<Line2D> iter = lineGen.axesIterator();

return iter;

}Incorporating LineGenerator into CartesianPlane

The first thing we can do in CartesianPlane is revise our instance variable declarations. We no longer need the grid width/height variables or min-/max-/center-coordinates. We do, however, need a rectangle that encapsulates those properties. We also need to add instance variables for drawing the labels on the x- and y-axes and a Font and FontRenderContext (we’ll discuss these below). That section of the class declaration now looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | /////////////////////////////////////////////////////// // // The following values are recalculated every time // paintComponent is invoked. // /////////////////////////////////////////////////////// private int currWidth; private int currHeight; private Graphics2D gtx; private Rectangle2D gridRect; private Font labelFont; private FontRenderContext labelFRC; |

Next, we can rewrite the logic to draw the grid lines and axes. The new code is shown below. Note that I have taken the liberty of renaming drawGrid to drawGridLines. Also, in drawGridLines I have added the logic to conditionally draw the grid lines based on the property gridLineDraw.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | private void drawAxes() { gtx.setColor( axisColor ); gtx.setStroke( new BasicStroke( axisWeight ) ); Iterator<Line2D> axes = LineGenerator.axesIterator( gridRect ); gtx.draw( axes.next() ); gtx.draw( axes.next() ); } private void drawGridLines() { if ( gridLineDraw ) { LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, gridLineLPU ); gtx.setStroke( new BasicStroke( gridLineWeight ) ); gtx.setColor( gridLineColor ); for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) gtx.draw( line ); } } |

Now that we have LineGenerator, adding the logic to draw the tic marks is straightforward.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | private void drawMinorTics() { if ( ticMinorDraw ) { LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, ticMinorMPU, ticMinorLen, LineGenerator.BOTH ); gtx.setStroke( new BasicStroke( ticMinorWeight ) ); gtx.setColor( ticMinorColor ); for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) gtx.draw( line ); } } private void drawMajorTics() { if ( ticMajorDraw ) { LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, ticMajorMPU, ticMajorLen, LineGenerator.BOTH ); gtx.setStroke( new BasicStroke( ticMajorWeight ) ); gtx.setColor( ticMajorColor ); for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) gtx.draw( line ); } } |

The next task will be to draw the labels. We’ll use two helper methods for this: drawHorizontalLabels and drawVerticalLabels. Before we get to those, however, let’s look at the final version (for this lesson) of paintComponent.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 | public void paintComponent( Graphics graphics ) { // begin boilerplate super.paintComponent( graphics ); currWidth = getWidth(); currHeight = getHeight(); gtx = (Graphics2D)graphics.create(); gtx.setColor( mwBGColor ); gtx.fillRect( 0, 0, currWidth, currHeight ); // end boilerplate // set up the label font // round font size to nearest int int fontSize = (int)(labelFontSize + .5); labelFont = new Font( labelFontName, labelFontStyle, fontSize ); gtx.setFont( labelFont ); labelFRC = gtx.getFontRenderContext(); // Describe the rectangle containing the grid float gridWidth = currWidth - marginLeftWidth - marginRightWidth; float minXco = marginLeftWidth; float gridHeight = currHeight - marginTopWidth - marginBottomWidth; float minYco = marginTopWidth; gridRect = new Rectangle2D.Float( minXco, minYco, gridWidth, gridHeight ); drawGridLines(); drawMinorTics(); drawMajorTics(); drawAxes(); drawHorizontalLabels(); drawVerticalLabels(); paintMargins(); // begin boilerplate gtx.dispose(); // end boilerplate } |

Drawing the Labels

Drawing the labels entails finding each major tic mark on the y-axis and vertically centering a label to the right of the tic mark. Likewise, we must find each major tic on the x-axis and horizontally center a label below it. As discussed in the Java Graphics Tools lesson, this requires finding the bounding rectangle of the label and correctly positioning its baseline. If you know much about font measurements, you might be aware that this process could be complicated by the descent (or descend) of the label, but numbers, +/- signs, and decimal points all live above the baseline, so we won’t have to worry about that. Also, the older, popular graphics facility for positioning text (based on the FontMetrics class) is flawed, so we’ll use the newer TextLayout facility.

The TextLayout Facility

To draw/measure text using the TextLayout facility, you need a Font, a Graphics2D, and a FontRenderContext. The Font and the FontRenderContext come from the Graphics2D. Once you have these three objects, you can get a TextLayout object. Then, you use the TextLayout object to obtain the bounding box (TextLayout.getBounds()) and draw the text (TextLayout.draw(Graphics2D g, float x, float y)). The x and y arguments passed to the draw method are the coordinates of the text’s baseline (for more about the baseline, see the Java Graphics Tools lesson). The sample code below was used to draw the figure at the left.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 | @Override public void paintComponent( Graphics graphics ) { //////////////////////////////////// // Begin boilerplate //////////////////////////////////// super.paintComponent( graphics ); gtx = (Graphics2D)graphics.create(); currWidth = getWidth(); currHeight = getHeight(); gtx.setColor( bgColor ); gtx.fillRect( 0, 0, currWidth, currHeight ); //////////////////////////////////// // End boiler plate //////////////////////////////////// gtx.setColor( Color.BLACK ); Font font = new Font( Font.MONOSPACED, Font.PLAIN, 25 ); gtx.setFont( font ); FontRenderContext frc = gtx.getFontRenderContext(); String label = "3.14159"; TextLayout layout = new TextLayout( label, font, frc ); Rectangle2D bounds = layout.getBounds(); float textXco = 50F; float textYco = 50F; layout.draw( gtx, textXco, textYco ); Rectangle2D rect = new Rectangle2D.Float( textXco + (float)bounds.getX(), textYco + (float)bounds.getY(), (float)bounds.getWidth(), (float)bounds.getHeight() ); gtx.draw( rect ); //////////////////////////////////// // Begin boilerplate //////////////////////////////////// gtx.dispose(); //////////////////////////////////// // End boiler plate //////////////////////////////////// } |

(About the above code: the x- and y- coordinates of the rectangle returned by getBounds are offsets from the baseline to the upper-left corner of the rectangle. The x value is typically negative, and the y value is typically 0. We won’t be using these values in our code.)

Labels on the Y-Axis

We’ll use LineGenerator to return a sequence of lines corresponding to the major tic marks on the y-axis. Recall that part of the iterator design is to return lines in order, from top to bottom. Also, part of the design is that the iterator for non-axial lines does not generate the lines x=0 or y=0. An annotated listing for the first part of this task, performed by drawHorizontalLabels, follows; see also Centering Text about a Line and Text Bounding Rectangle.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | /** * Draw the labels on the horizontal tic marks * (top to bottom of y-axis). */ private void drawHorizontalLabels() { // padding between tic mark and label final int labelPadding = 3; LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, ticMajorMPU, ticMajorLen, LineGenerator.HORIZONTAL ); float spacing = gridUnit / ticMajorMPU; float labelIncr = 1 / ticMajorMPU; float originYco = (float)gridRect.getCenterY(); for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) { // ... } } |

- Line 8: This is the padding to insert between a tic mark and its label.

- Lines 10-17: Create a generator for horizontal lines, specifying the number of tics per unit (ticMajorMPU) and the length of a major tic (ticMajorLen).

- Line 18: Calculate the number of pixels between each tic mark.

- Line 19: Calculate the number of units a major tic mark represents. For example, if there are two tics for each unit, this will be .5; if there are .5 tics for each unit, this will be 2.

- Line 20: Get the y-coordinate for the y-axis.

- Line 21: Iterate over the list of lines (see below).

Inside the loop, for each line, we have to calculate the x- and y-coordinates of the baseline of the label and the unit value of the tic mark (for example, .5, 1, 1.5, etc). The unit value of the tic mark is found by calculating the distance between the tic mark and the x-axis. The x-coordinate is the x-coordinate of the right end of the tic mark + the label margin. The y-coordinate is the y-coordinate of the tic mark + half the height of the label’s bounding rectangle. To get the bounding rectangle and draw the label, we will need the current Font and the FontRenderContext; recall that these are obtained each time the paintComponent method is invoked:

int fontSize = (int)(labelFontSize + .5);

labelFont = new Font( labelFontName, labelFontStyle, fontSize );

gtx.setFont( labelFont );

labelFRC = gtx.getFontRenderContext();At the bottom of the loop, we calculate the value of the next label to draw. Here’s an annotated listing for the loop.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) { float xco2 = (float)line.getX2(); float yco1 = (float)line.getY1(); int dist = (int)((originYco - yco1) / spacing); float next = dist * labelIncr; String label = String.format( "%3.2f", next ); TextLayout layout = new TextLayout( label, labelFont, labelFRC ); Rectangle2D bounds = layout.getBounds(); float yOffset = (float)(bounds.getHeight() / 2); float xco = xco2 + labelPadding; float yco = yco1 + yOffset; layout.draw( gtx, xco, yco ); } |

- Line 3: Get the x-coordinate of the right-hand end of the tic mark.

- Line 4: Get the y-coordinate of the tic mark.

- Line 5: Get the distance, in tic marks, between the x-axis and the tic mark we are labeling. The figure (originYco – yco1) is the distance in pixels; note that if the tic mark is above the x-axis, this is a positive value, and if the tic mark is below the x-axis, it’s a negative value. Dividing by the spacing between tic marks gives us the distance in tic marks.

- Line 6: Calculate the unit value of the tic mark.

- Line 7: Format the unit value as a string with two digits past the decimal point.

- Lines 8-10: Get the textLayout object and obtain the bounding rectangle of the string.

- Line 11: Calculate the y-offset that will center the label with respect to the horizontal tic mark to its left.

- Line 12: Calculate the label’s x-coordinate, which is slightly to the right of the tic mark.

- Line 13: Calculate the label’s y-coordinate, which is the y-coordinate of the tic mark adjusted by one-half the height of the label’s bounding box.

- Line 14: Draw the label.

Labels on the X-Axis

Drawing the labels on the vertical tic marks (on the x-axis) is similar. The main difference is that the y-coordinate label’s baseline will be the y-coordinate of the lower end of the tic mark plus the height of the label’s bounding rectangle plus padding. The x-coordinate is the x-coordinate of the tic mark less half the width of the bounding rectangle. The code follows below.

Note: the student is encouraged to attempt to write this method before looking at the solution provided.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 | private void drawVerticalLabels() { // padding between tic mark and label final int labelPadding = 3; LineGenerator lineGen = new LineGenerator( gridRect, gridUnit, ticMajorMPU, ticMajorLen, LineGenerator.VERTICAL ); float spacing = gridUnit / ticMajorMPU; float labelIncr = 1 / ticMajorMPU; float originXco = (float)gridRect.getCenterX(); for ( Line2D line : lineGen ) { float xco1 = (float)line.getX2(); int dist = (int)((xco1 - originXco) / spacing); float next = dist * labelIncr; String label = String.format( "%3.2f", next ); TextLayout layout = new TextLayout( label, labelFont, labelFRC ); Rectangle2D bounds = layout.getBounds(); float yOffset = (float)(bounds.getHeight() + labelPadding); float xOffset = (float)(bounds.getWidth() / 2); float xco = xco1 - xOffset; float yco = (float)line.getY2() + yOffset; layout.draw( gtx, xco, yco ); } } |

Short of plotting a curve, that’s the code for displaying our Cartesian plane. In our lessons, we have much to do before we get to plotting, including documentation, testing, and property management. I understand, however, if you’re chomping at the bit and are ready for some visual results. If so, I encourage you to add some simple plotting code to CartesianPlane and a main method that plots a simple curve. I have done so in the GitHub repository in the classes CartesianPlaneTemp and MainTemp.

Summary

This lesson considered several topics, including encapsulation, inner classes, iterators, iterables, and drawing text with the TextLayout facility. In the next lesson, we’ll discuss documentation, specifically the Javadoc facility for writing documentation in-line with your code.