This lesson is about anonymous classes and their use in Java programming, which gets us into various interesting topics. Since Java 8, the syntax used to declare and instantiate anonymous classes has been extended to the declaration of lambdas. Lambdas are particularly useful for creating functional interfaces, a kind of interface with exactly one abstract method. Functional interfaces lead naturally to a discussion of streams, both of which were added in Java 8, along with lambda syntax and significant changes to how interfaces are declared. We’ll be talking about all of these topics.

Here are some links to additional resources regarding these subjects.

From Oracle Corporation:

- Anonymous Classes (Tutorial)

- Lambda Expressions (Tutorial)

- Method References (Tutorial)

- Java 8: Lambdas, Part 1

- Java 8: Lambdas, Part 2

- Interfaces (Tutorial)

- Package java.util.function (Javadoc)

- Aggregate Operations (Tutorial)

- Parallelism (Tutorial)

All of the sample code in the following sections can be found in the GitHub repository for this project.

GitHub repository: Anonymous Classes

Anonymous Classes

As the name implies, an anonymous class is a class without a name. It is declared and instantiated simultaneously. Anonymous classes always subclass an existing class or implement an interface. Typically, they override one or more methods in the superclass or interface.

According to Oracle, anonymous classes are most useful when you need one instance of a new class. Before looking at an example of an anonymous class, let’s develop an example using a traditional (named) nested class to perform limited operations. SortingExampleInteger1, from the project’s basics package, is a program that generates a random list of integers, then uses a Comparator<Integer>, implemented as a nested class, to sort the list in reverse order.

Review: Comparator<T> is an interface with one abstract method: int compare(T o1, T o2)

This method returns a positive integer if o1 is greater than o2, a negative integer if o2 is greater than o1, and 0 if the two objects are equal. A common example of a similar method is String.compareTo(String). For further information, see the Comparator Javadoc Page.

List.sort(Comparator<T> cmp) is a method declared by the List<T> interface that sorts a list according to the comparison rule implemented by cmp.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 | public class SortingExampleInteger1 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Integer> randomList = new ArrayList<>(); Random randy = new Random( 0 ); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 100 ; ++inx ) randomList.add( randy.nextInt( 100 ) ); Comparator<Integer> comp = new ReverseSorter(); randomList.sort( comp ); for ( Integer num : randomList ) System.out.println( num ); } private static class ReverseSorter implements Comparator<Integer> { public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 ) { int rcode = num2 - num1; return rcode; } } } |

The explicit declaration of ReverseSorter in the above example can be replaced with an anonymous class declaration/instantiation. You declare and instantiate an anonymous class with an expression beginning with the new operator. This is followed by Type(), just as if you were instantiating a class (new is used whether you are subclassing a class or implementing an interface). This is followed by a block statement that contains your code, following is an example of an expression that can be used to instantiate an anonymous class:

new Comparator<Integer>()

{

public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 )

{

int rcode = num2 - num1;

return rcode;

}

}Note that this is an expression of type Comparator<Integer> and can be used anywhere such an expression is valid, for example, in an expression statement (see SortingExampleInteger2 in the project’s basics package):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | Comparator<Integer> comp = new Comparator<Integer>() { public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 ) { int rcode = num2 - num1; return rcode; } }; randomList.sort( comp ); |

(Note that expression statements end with a semicolon, which explains the ‘;’ at the end of line 9.) But an expression, correctly used, can be an argument in a method invocation, so we can omit the explicit declaration altogether, giving us the final sample program as follows (see SortingExampleInteger3 in the project’s basics package):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | public class SortingExampleInteger3 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Integer> randomList = new ArrayList<>(); Random randy = new Random( 0 ); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 100 ; ++inx ) randomList.add( randy.nextInt( 100 ) ); randomList.sort( new Comparator<Integer>() { public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 ) { int rcode = num2 - num1; return rcode; } } ); for ( Integer num : randomList ) System.out.println( num ); } } |

Of course, when you’re reading someone else’s code, you will rarely see the method invocation laid out in such a nice, organized arrangement; you are far more likely to see something like: randomList.sort(new Comparator<Integer>(){

public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 ){

int rcode = num2 - num1; return rcode;}});

As you write your first few examples of anonymous classes, I suggest you use a format similar to the one in SortingExampleInteger3 to keep things straight in your mind.

Let’s do one more example. SortingExampleString1 is a program that uses a traditional nested class to perform a case-insensitive string sort.

Review: By default, Strings are sorted according to their Unicode values. Since ‘A’ has a Unicode value of 65, and ‘a’ has a Unicode value of 97, “Zebra” would be considered less than “aardvark” and would come first in a sorted list. But if you performed a case-insensitive sort, “Zebra” would come after “aardvark” because ‘Z’ (or ‘z’) comes after ‘a’ (or ‘A’) in the alphabet. The method String.compareTo(String) performs a default comparison; String.compareToIgnoreCase(String) performs a case-insensitive comparison.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | public class SortingExampleString1 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> randomList = new ArrayList<>(); Random randy = new Random( 0 ); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 100 ; ++inx ) { int rInt = randy.nextInt( 100 ); String str = rInt % 2 == 0 ? "ITEM" : "item"; String item = String.format( "%s: %03d", str, rInt ); randomList.add( item ); } Comparator<String> comp = new InsensitiveSorter(); randomList.sort( comp ); for ( String str : randomList ) System.out.println( str ); } private static class InsensitiveSorter implements Comparator<String> { public int compare( String str1, String str2 ) { return str1.compareToIgnoreCase( str2 ); } } } |

Suggested exercises:

-

- Following the example in SortingExampleInteger2, replace the explicit declaration of InsensitiveSorter in the above code with an anonymous class declaration in an expression statement:

Comparator<String> comp = new Comparator<>()...

Then, use the anonymous class instance to sort the list of Strings. - Following the example in SortingExampleInteger3, remove the expression statement and instantiate the comparator directly as an argument to the sort method:

randomList.sort( new Comparator<String>(){....

- Following the example in SortingExampleInteger2, replace the explicit declaration of InsensitiveSorter in the above code with an anonymous class declaration in an expression statement:

The program SortingExampleString1 uses an explicitly declared Comparator<String> class to perform a case-insensitive string sort. SortingExampleString2 replaces the explicitly declared class with an anonymous class declared as an expression and assigned to a variable:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | Comparator<String> comp = new Comparator<>() { public int compare( String str1, String str2 ) { return str1.compareToIgnoreCase( str2 ); } }; randomList.sort( comp ); |

The final program, SortingExampleString3, eliminates the variable. It uses a Comparator<String> declaration/instantiation as an argument to the sort method. It looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 | public class SortingExampleString3 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<String> randomList = new ArrayList<>(); Random randy = new Random( 0 ); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 100 ; ++inx ) { int rInt = randy.nextInt( 100 ); String str = rInt % 2 == 0 ? "ITEM" : "item"; String item = String.format( "%s: %03d", str, rInt ); randomList.add( item ); } randomList.sort( new Comparator<String>() { public int compare( String str1, String str2 ) { return str1.compareToIgnoreCase( str2 ); } } ); for ( String str : randomList ) System.out.println( str ); } } |

Here are two more examples of anonymous classes. In OverridingExample1 and OverridingExample2, processQueue is an instance of an anonymous class, a subclass of ArrayList. OverridingExample1 overrides the add and remove methods to log each invocation of these methods. OverridingExample2 overrides the remove method to prevent list elements from being deleted. (OverridingExample2 is the start of an example of creating a list that can be extended but not otherwise modified; in practice, we have a lot more overriding to do before reaching this goal.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 | public class OverridingExample1 { @SuppressWarnings("serial") private static final List<String> processQueue = new ArrayList<>() { @Override public boolean add( String str ) { System.err.println( "added: " + str ); return super.add( str ); } @Override public String remove( int index ) { String str = super.remove( index ); System.err.println( "removed: " + str ); return str; } }; public static void main(String[] args) { Random randy = new Random( 0 ); int itemNum = 0; while ( itemNum < 10 ) { String item = String.format( "item: %03d", itemNum++ ); processQueue.add( item ); item = String.format( "item: %03d", itemNum++ ); processQueue.add( item ); int index = randy.nextInt( processQueue.size() ); processQueue.remove( index ); } } } |

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | public class OverridingExample2 { @SuppressWarnings("serial") private static final List<String> processQueue = new ArrayList<>() { @Override public String remove( int index ) { throw new UnsupportedOperationException(); } }; public static void main(String[] args) { Random randy = new Random( 0 ); int itemNum = 0; while ( itemNum < 10 ) { String item = String.format( "item: %03d", itemNum++ ); processQueue.add( item ); item = String.format( "item: %03d", itemNum++ ); processQueue.add( item ); int index = randy.nextInt( processQueue.size() ); processQueue.remove( index ); } } } |

Lambdas

|

PointSorterA public static void main(String[] args)

{

Point origin = new Point( 0, 0 );

List<Point> points = new ArrayList<>();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 25 ; ++inx )

points.add( Utils.randomPoint() );

points.sort( new Comparator<Point>() {

public int compare( Point p1, Point p2 )

{

double p1Dist = origin.distance( p1 );

double p2Dist = origin.distance( p2 );

int result = (int)(p1Dist - p2Dist);

return result;

}

});

for ( Point point : points )

System.out.println( point );

}

|

PointSorterB public static void main( String[] args )

{

Point origin = new Point( 0, 0 );

List<Point> points = new ArrayList<>();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 25 ; ++inx )

points.add( Utils.randomPoint() );

Comparator<Point> comp =

new Comparator<Point>() {

public int compare( Point p1, Point p2 )

{

double p1Dist = origin.distance( p1 );

double p2Dist = origin.distance( p2 );

int result = (int)(p1Dist - p2Dist);

return result;

}

};

points.sort( comp );

for ( Point point : points )

System.out.println( point );

}

|

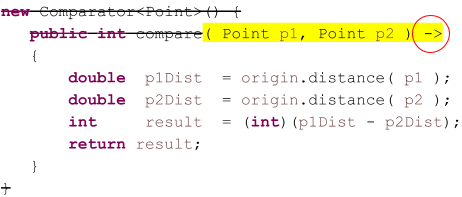

The following discussion refers to the figure above, which illustrates two versions of a program to sort a list of Cartesian coordinates by their distance from the origin. Point is a class that encapsulates a pair of (x,y) coordinates; it is contained in the package java.awt. The method distance(Point) in the Point class calculates the distance between this Point and the given Point. Utils.randomPoint() is a method that creates a Point object with coordinates in the range [-100,100]; its code is in the GitHub repository.

A lambda is a shortcut for creating an anonymous class based on an interface with exactly one abstract method. Suppose we have a Comparator<Integer> that sorts pairs of coordinates based on their distance from the origin, as shown in the figure above.

Theoretically, could we persuade the compiler to perform some of this work on our behalf?

- Based on the above figure, which uses an anonymous class to sort a list of points:

- In PointSorterA, the compiler knows the List.sort method requires an argument of type Comparator<Point>. Potentially, the compiler could insert the new Comparator<Point>() invocation, eliminating the need for us to write it ourselves.

- In the declaration of comp in PointSorterB, the compiler knows from the left side of the equal sign that the right side has to start with a new Comparator <Point>(). Potentially, the compiler could insert the new Comparator<Point>() invocation, eliminating the need for us to write it ourselves.

- Knowing that the Comparator<Point> instance has a single abstract method, it could anticipate the block statement comprising the body of the anonymous class, eliminating the need for us to insert the outer braces ({}).

- Knowing that the signature of the single abstract method is compare( Point, Point), the compiler could fill in the method declaration for us; the only thing it can’t figure out by itself is the parameter declarations.

Suppose we were to provide the compiler with the declarations of the parameters using this syntax: (Point p1, Point p2) ->

Then, the compiler could automatically generate a) new Comparator<Point>, b) the delimiters of the anonymous class body ({}), and c) the compare method declaration, leaving us to provide just the body of the method. For example, in PointSorterA:

points.sort( (Point p1, Point p2) -> {

double p1Dist = origin.distance( p1 );

double p2Dist = origin.distance( p2 );

int result = (int)(p1Dist - p2Dist);

return result;

});And in PointSorterB:

Comparator<Point> comp = (Point p1, Point p2) -> {

double p1Dist = origin.distance( p1 );

double p2Dist = origin.distance( p2 );

int result = (int)(p1Dist - p2Dist);

return result;

};

points.sort( comp );⏹ Another shortcut: if the compiler can anticipate the parameter types (which is usually the case), we don’t have to declare them:

Comparator<Point> comp = (p1,p2) -> {

double p1Dist = origin.distance( p1 );

double p2Dist = origin.distance( p2 );

int result = (int)(p1Dist - p2Dist);

return result;

};

points.sort( comp );⬛ Lambda Syntax

If an anonymous class encapsulates an instance of an interface with a single method, we can declare/instantiate the anonymous class using a lambda of the form:

(p0, …, pn) -> { body of method }

🔲 More Shortcuts

Lambdas are all about shortcuts, so there are a few more variations for writing them. Here are two additional examples: the code on the left illustrates the traditional implementation of an anonymous class, and the code on the right demonstrates the lambda alternative.

|

IntSorterA public static void main(String[] args)

{

Random randy = new Random( 0 );

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<>();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 25 ; ++inx )

numbers.add( randy.nextInt( 200 ) - 100 );

numbers.sort( new Comparator<Integer>() {

public int compare( Integer num1, Integer num2 )

{

return num2 - num1;

}

});

for ( Integer num : numbers )

System.out.println( num );

}

|

IntSorterA1 public static void main(String[] args)

{

Random randy = new Random( 0 );

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<>();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 25 ; ++inx )

numbers.add( randy.nextInt( 200 ) - 100 );

numbers.sort( (num1,num2) -> {

return num2 - num1;

});

for ( Integer num : numbers )

System.out.println( num );

}

|

⏹ Method Body Consisting of a Single Statement

If the entire body of the method can be expressed as a single statement, you can eliminate the braces around the method body and the semicolon at the end of the statement. If the statement is a return statement, you can eliminate the return keyword. (p0, …, pn) -> { body of method } (p0, …, pn) -> statement (p0, …, pn) -> expression

With this shortcut, the lambda in class IntSorterA1 above can be expressed like this: (num1,num2) -> num2 - num1

and as shown below.

public static void main(String[] args)

{

Random randy = new Random( 0 );

List<Integer> numbers = new ArrayList<>();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 25 ; ++inx )

numbers.add( randy.nextInt( 200 ) - 100 );

numbers.sort( (num1,num2) -> num2 - num1 );

for ( Integer num : numbers )

System.out.println( num );

}⏹ Methods with Exactly One Parameter

If a method has a single parameter, the parentheses on the left side of the arrow can be eliminated. p -> { body of method } p -> statement p -> expression

The List<T> interface has a method, forEach, with the signature: forEach(Consumer<T> action)

Consumer<T> is an interface with a single method: void accept( T t )

The forEach method traverses the list, passing each element to the accept method of the Consumer<T> interface. Using the forEach method, the for loops at the end of the IntSorter examples can be implemented using the forEach method and an anonymous class, as shown below. The traditional implementation is on the left, and the lambda equivalent is on the right.

|

IntSorterA numbers.forEach( new Consumer<Integer>() {

public void accept( Integer p ){

System.out.println( p );

}

});

|

IntSorterA1 numbers.forEach( p -> System.out.println( p ) ); |

🔲 Lambda Syntax Examples

Here are four ways to declare/instantiate an anonymous class to perform a case-insensitive string sort. They are all equivalent. The first provides a traditional anonymous class declaration, the second uses a long-form lambda, and the third uses a lambda with all syntactical shortcuts applied. The fourth example uses the same syntax as the third but instantiates the comparator directly as an argument to a sort method.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | private static final Comparator<String> insensitiveCmp1 = new Comparator<String>() { public int compare( String s1, String s2 ) { return s1.compareToIgnoreCase( s2 ); } }; private static final Comparator<String> insensitiveCmp2 = (s1, s2) -> { return s1.compareToIgnoreCase( s2 ); }; private static final Comparator<String> insensitiveCmp3 = (s1, s2) -> s1.compareToIgnoreCase( s2 ); randomList.sort( (s1, s2) -> s1.compareToIgnoreCase( s2 ) ); |

Here’s another example that borrows from the Root and Canvas classes in the Java Graphics Bootstrap tutorial; the code for this example, before substituting an anonymous class, looks like this (from the class LambdaFramePart1 in our project source tree):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 | public static void main(String[] args) { SwingUtilities.invokeLater( new Root() ); } private static class Root implements Runnable { public void run() { JFrame frame = new JFrame(); frame.setContentPane( new Canvas() ); frame.pack(); frame.setVisible( true ); } } @SuppressWarnings("serial") private static class Canvas extends JPanel { // ... } } |

For brevity, I have omitted the body of the Canvas class; if you want to see it, you can find it in the GitHub repository. The important thing here is that the argument to SwingUtilities.invokeLater is an object that implements the Runnable interface. This interface has a single abstract method with the signature public void run(). Using lambdas, we can eliminate the explicit declaration of the Root class and substitute this (see LambdaFramePart2):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | public class LambdaFramePart2 { public static void main(String[] args) { SwingUtilities.invokeLater( () -> { JFrame frame = new JFrame(); frame.setContentPane( new Canvas() ); frame.pack(); frame.setVisible( true ); } ); } @SuppressWarnings("serial") private static class Canvas extends JPanel { // ... } } |

For the record, I find this syntax a bit awkward, especially since the body of the Runnable’s run method is usually much more complex than the given four lines of code. When writing code to instantiate a new frame, I would be more likely to use something that looks like this (LambdaFramePart3):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | public static void main(String[] args) { SwingUtilities.invokeLater( () -> buildGUI() ); } private static void buildGUI() { JFrame frame = new JFrame(); frame.setContentPane( new Canvas() ); frame.pack(); frame.setVisible( true ); } |

Here’s one more example utilizing a PropertyListener:

In case you don’t know what a PropertyListener is:

Some classes have a mechanism for notifying users when a property has changed. An example would be the background color of a window changing from light gray to dark gray. You don’t need to know all the details of PropertyListeners to understand this example. The salient points are:

-

- To be informed of a property change, you must implement the interface PropertyChangeListener…

- … this interface has one abstract method, making it a good target for implementation as a lambda…

- … the method has a single parameter, making it ideal for use in this particular example; the method is:

public void propertyChange(PropertyChangeEvent evt) - … a PropertyChangeEvent object contains the name of the changed property, its old value (the value the property was changed from), and the new value (the value the property was changed to).

For more information, see the PropertyChangeListener Javadoc and How to Write a Property Change Listener from the Oracle Java Tutorial. See this website’s Cartesian Plane Lesson 7: Property Management (Page 1) tutorial.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 | public class LambdaFramePart4 { public static void main(String[] args) { SwingUtilities.invokeLater( () -> buildGUI() ); } private static void buildGUI() { JFrame frame = new JFrame(); frame.addPropertyChangeListener( new PropertyMonitor() ); frame.setContentPane( new Canvas() ); frame.pack(); frame.setVisible( true ); } private static class PropertyMonitor implements PropertyChangeListener { @Override public void propertyChange(PropertyChangeEvent evt) { System.out.println( evt.getPropertyName() + " changed from " + evt.getOldValue() + " to " + evt.getNewValue() ); } } // ... } |

Here is the same functionality with the explicit PropertyChangeListener declaration replaced by a lambda.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | public class LambdaFramePart5 { public static void main(String[] args) { SwingUtilities.invokeLater( () -> buildGUI() ); } private static void buildGUI() { JFrame frame = new JFrame(); frame.addPropertyChangeListener( e -> System.out.println( e.getPropertyName() + " changed from " + e.getOldValue() + " to " + e.getNewValue() ) ); frame.setContentPane( new Canvas() ); frame.pack(); frame.setVisible( true ); } // ... } |

⬛ Method References

One more convenient shortcut for writing lambdas is the method reference. To demonstrate how this works, let’s develop the ShowDog class. This class has four instance variables that describe a dog appearing in a show: the dog’s name, age, breed, and the ID of its owner. Here’s part of the class declaration:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 | public class ShowDog { private final String name; private final int age; private final String breed; private final int ownerID; public ShowDog(String name, int age, String breed, int ownerID) { super(); this.name = name; this.age = age; this.breed = breed; this.ownerID = ownerID; } @Override public String toString() { StringBuilder bldr = new StringBuilder(); bldr.append( "Name: " ).append( name ).append( "," ) .append( "age: " ).append( age ).append( "," ) .append( "breed:" ).append( breed ).append( "," ) .append( "owner: " ).append( ownerID ); return bldr.toString(); } // ... } |

The class also has four methods that conform to the signature of the compare method required by the Comparator<T> interface. They can be used to compare two show dogs by name, age, breed, or owner ID. They look like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | // ... public static int sortByName( ShowDog dog1, ShowDog dog2 ) { return dog1.name.compareTo( dog2.name ); } public static int sortByBreed( ShowDog dog1, ShowDog dog2 ) { return dog1.breed.compareTo( dog2.breed ); } public static int sortByAge( ShowDog dog1, ShowDog dog2 ) { return dog1.age - dog2.age; } public static int sortByOwnerID( ShowDog dog1, ShowDog dog2 ) { return dog1.ownerID - dog2.ownerID; } // ... |

These methods are convenient for use in Comparator<ShowDog> anonymous classes constructed from lambdas and are used to sort lists of ShowDogs in various ways, such as the following:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 | public class MethodReferenceExample2 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<ShowDog> list = getList(); System.out.println( "*** sort by age ***" ); list.sort( (d1, d2) -> ShowDog.sortByAge( d1, d2 ) ); for ( ShowDog dog : list ) System.out.println( dog ); System.out.println( "*** sort by breed ***" ); list.sort( (d1,d2) -> ShowDog.sortByBreed(d1, d2) ); for ( ShowDog dog : list ) System.out.println( dog ); } private static List<ShowDog> getList() { List<ShowDog> list = new ArrayList<>(); list.add( new ShowDog( "Fido", 3, "Collie", 55555 ) ); list.add( new ShowDog( "Shep", 2, "Collie", 22222 ) ); list.add( new ShowDog( "Tipsy", 4, "Poodle", 33333 ) ); list.add( new ShowDog( "Doodles", 5, "Shepherd", 77777 ) ); list.add( new ShowDog( "Iggy", 2, "Poodle", 33333 ) ); return list; } } |

Because the lambda has two parameters passed directly to an existing method, we can construct the lambda using a method reference. Using the syntax of a method reference, we can eliminate all mention of parameters. The syntax is class-name::method-name for class methods, or object-name::method-name for instance methods, for example: ShowDog::sortByBreed

System.out::println

Using method references, the two lambdas in the above example can be rewritten as shown here:

Original form:list.sort( (d1, d2) -> ShowDog.sortByAge( d1, d2 ) );

list.sort( (d1,d2) -> ShowDog.sortByBreed(d1, d2) );

Using method references:list.sort( ShowDog::sortByAge );

list.sort( ShowDog::sortByBreed );

Here is our previous example modified to use method references.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | public static void main(String[] args) { List<ShowDog> list = getList(); System.out.println( "*** sort by age ***" ); list.sort( ShowDog::sortByAge ); for ( ShowDog dog : list ) System.out.println( dog ); System.out.println( "*** sort by breed ***" ); list.sort( ShowDog::sortByBreed ); for ( ShowDog dog : list ) System.out.println( dog ); } |

Take note, all you aging C programmers who always wished Java had pointers to functions.

Note that the for-loops in the above example can also be written using the List.forEach method, and lambdas implemented as method references: list.forEach( System.out::println );

In addition to method references, you can also have constructor references. The syntax is Class::new, for example, ArrayList<>::new. There’s an example of the use of a constructor reference below.

Functional Interfaces

After discussing lambdas, we must discuss functional interfaces; they were literally made for each other. First, let’s define the terms ‘function’ and ‘functional interface’ as used in this context.

Function: an organized unit of logic dedicated to a specific task and deterministic (producing predictable results) in nature. In programming, a function can be composed of a method (or subroutine, procedure, or function, depending on your language preference) or a simple block of code, such as may be used in a lambda. A function always produces a result, even if it’s the null result. A function may or may not require arguments.

Functional Interface: In Java, this must be an interface, such as the Runnable interface. The interface must have precisely one abstract method. In the Java documentation, many such interfaces, such as Runnable, are annotated with the @FunctionalInterface tag; however, many other interfaces qualify as functional even though they are not annotated in this manner; these include, for example, ActionListener and PropertyChangeListener.

We’ve used functional interfaces above, for example, whenever we used List.sort, List.forEach, or SwingUtilities.invokeLater. The signatures of these three methods look like this:

- List.sort( Comparator<T> )

Comparator<T> is an interface whose sole abstract method is int compare(T t1, T t2). Two (equivalent) examples of using a Comparator<String> are shown below:randomList.sort( (s1, s2) ->

s1.compareToIgnoreCase( s2 )

);randomList.sort( String::compareToIgnoreCase );

- List.forEach( Consumer<T> action )

Consumer<T> is an interface whose sole abstract method is void accept( T t ). Two (equivalent) examples of its use are:randomList.forEach( t -> System.out.println( t );randomList.forEach( System.out::println );

- SwingUtilities.invokeLater( Runnable runnable )

Runnable is an interface with a single abstract method, void run(). Two (equivalent) examples of its use are:SwingUtilities.invokeLater( () -> buildGUI() );- SwingUtilities.invokeLater( LambaFrame3::buildGUI );

Java’s java.util.function package contains functional interface declarations that are convenient to use in many familiar programming contexts. The Javadoc page for this package lists what, at first glance, appears to be an overwhelming number of interfaces, but it’s not as bad as it looks. They all fall into just a handful of categories, and most are specializations declared for convenience. Some of the categories are:

Function: A function consumes one or more arguments and produces a result. Examples of expressions encapsulated in a function are y = f(x) and z = f(x,y). A partial list of interfaces representing functions includes:

- Function<T,R>. This interface describes a function that requires one argument of type T, and produces a result of type R. Its single abstract method is public R apply(T t). Specializations of this interface include:

- IntFunction<R>: a function that requires an int argument and produces a result of type R. Abstract method: public R apply(int t).

- IntToDoubleFunction: a function that requires an int argument and produces a result of type double. Abstract method: public double applyAsDouble(int t).

- IntToLongFunction: a function that requires an int argument and produces a result of type long. Abstract method: public long applyAsLong(int t)

- LongFunction<R>: a function that requires a long argument and produces a result of type R. Abstract method: public R apply(long t)

- LongToIntFunction: a function that requires a long argument and produces a result of type int. Abstract method: public int applyAsInt(long t)

- BiFunction<T,U,R>. This interface describes a function that requires two arguments of type T and U and produces a result of type R. Abstract method: public R apply(T t, U u). Specializations of this interface include:

- ToDoubleBiFunction<T,U>: a function that requires two arguments of type T and U and produces a result of type double. Abstract method: double applyAsDouble(T t, U u)

- ToIntBiFunction<T,U>: a function that requires two arguments of type T and U and produces a result of type int. Abstract method: int applyAsInt(T t, U u)

- UnaryOperator<T>. This interface describes a function that requires one argument and produces a result, each of type T. Abstract method: public T apply(T t)

- BinaryOperator<T>. This interface describes a function that requires two arguments and produces a result, all of type T. Abstract method: public T apply(T t, T u). Specializations of this interface include:

- DoubleBinaryOperator: a function that requires two arguments of type double and produces a result of type double. Abstract method: double applyAsDouble(double left, double right)

- IntBinaryOperator: a function that requires two arguments of type int and produces a result of type int. Abstract method: double applyAsInt(int left, int right)

- LongBinaryOperator: a function that requires two arguments of type long and produces a result of type long. Abstract method: long applyAsLong(long left, long right)

Predicate: A predicate consumes one or more arguments and produces a Boolean result. Examples of expressions encapsulated in a predicate are y < x and z > x + y. A partial list of interfaces representing predicates includes:

- Predicate<T>. This interface describes a function that requires one argument of type T and produces a result of type boolean. Abstract method: public boolean test(T t). Specializations of this interface include:

- DoublePredicate: a function that requires one argument of type double and produces a result of type boolean. Abstract method: public boolean test(double arg)

- IntPredicate: a function that requires one argument of type int and produces a result of type boolean. Abstract method: public boolean test(int arg)

- BiPredicate<T,U>. This interface describes a function that requires two arguments of type T and U and produces a result of type boolean. Abstract method: public boolean test(T t, U u).

Consumers and Suppliers

A consumer is a function that takes one or more arguments and returns nothing (type void, a.k.a. the null result). A supplier requires zero arguments and returns a non-void value. Examples of consumers are setters: void set(int arg) and void setName(String last, String first). Examples of suppliers include getters: int getRadius() and double getAverage(). A partial list of interfaces encapsulating consumers and suppliers includes:

- Consumer<T>. This interface describes a function that requires one argument of type T and produces a void result. Abstract method: public void accept(T t). Specializations of this interface include:

- IntConsumer

- DoubleConsumer

- LongConsumer

- BiConsumer<T,U>. This interface describes a function that requires two arguments of type T and U and produces a void result. Abstract method: public void accept(T t, U u).

- Supplier<T>. This interface describes a function that requires no arguments and produces a result of type T. Abstract method: public T get(). Specializations of this interface include:

- IntSupplier: Abstract method: public int getAsInt().

- LongSupplier: Abstract method: public long getAsLong().

- BooleanSupplier: Abstract method: public boolean getAsBoolean().

⬛ Implementing Functional Interfaces

Below is a discussion of using functional interfaces when designing a class or method.

⏹ PrimeSupplier is an example of a Supplier implementation. It implements IntSupplier, providing the required implementation of getAsInt. Here’s the class and an example of its use.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 | class PrimeSupplier implements IntSupplier { private int next = 2; @Override public int getAsInt() { int result = next; nextPrime(); return result; } private void nextPrime() { if ( next == 2 ) next = 3; else { int test; for ( test = next + 2 ; !isPrime( test ) ; test += 2 ) ; next = test; } } private static boolean isPrime( int num ) { boolean result = true; if ( num < 2 ) result = false; else if ( num == 2 ) result = true; else if ( num % 2 == 0 ) result = false; else { int limit = (int)Math.sqrt( num ) + 1; for ( int test = 3 ; result && test <= limit ; test += 2 ) result = num % test != 0; } return result; } } |

public static void main(String[] args)

{

// Print a list of the first 100 prime numbers

IntSupplier supplier = new PrimeSupplier();

for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < 100 ; ++inx )

System.out.println( supplier.getAsInt() );

}⏹ The sample class Polynomial has a method plot that requires a DoubleSupplier as an argument. It uses the supplier to obtain a sequence of x values and computes (according to the encapsulated polynomial) the corresponding y values, returning a list of x/y pairs. It looks like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 | public class Polynomial { private final double[] coefficients; public Polynomial( double... coeff ) { coefficients = Arrays.copyOf( coeff, coeff.length ); } public double evaluate( double xval ) { int degree = coefficients.length - 1; double yval = 0; for ( double coeff : coefficients ) yval += coeff * Math.pow( xval, degree-- ); return yval; } public List<Point2D> plot( int numPoints, DoubleSupplier supplier ) { List<Point2D> points = new ArrayList<>(); for ( int inx = 0 ; inx < numPoints ; ++inx ) { double xval = supplier.getAsDouble(); double yval = evaluate( xval ); points.add( new Point2D.Double( xval, yval ) ); } return points; } } |

The sample program DoubleSupplierDemo contains a nested class, XGenerator, that implements the DoubleSupplier interface. Given a starting point and increment, it generates a sequence of values of type double; the next value in the sequence is generated by applying the increment to the previous value. An instance of this class is passed to the plot method of the Polynomial class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 | public class DoubleSupplierDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { Polynomial poly = new Polynomial( 2, 3, 1 ); List<Point2D> points = poly.plot( 10, new XGenerator( -2, .5 ) ); points.forEach( p -> System.out.println( p.getX() + "->" + p.getY() ) ); } private static class XGenerator implements DoubleSupplier { private final double incr; private double next; public XGenerator( double start, double incr ) { this.next = start; this.incr = incr; } @Override public double getAsDouble() { double val = next; next += incr; return val; } } } |

⏹ The main method of the sample program ConsumerDemo is sending a message through a corporate service. The main method identifies the source, destination, and content of the message. The message must now be packaged for transmission; this includes formatting the creation date according to corporate standards, calculating a checksum, and many other details the typical programmer is not expected to be aware of. The packaging is accomplished by the dispatch method. After packaging, the message will be scheduled for transmission via a designated corporate service, which might include:

- The high-priority email server

- The log server

- The secure email server

- The notification server

- The scheduling server

- etc.

The message is sent to the dispatch method along with a Consumer<Message> object that identifies the designated service: Message message = new Message( src, dst, txt );

dispatch( message, LocalDispatchService::secureMailer );

(As noted above, the dispatch method does not transmit the message immediately. It’s more like mailing a letter. You put a letter in a mailbox, then go about your business. Sometime later, the postal service collects the letter and delivers it to its destination.)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | public class LocalDispatchService { public static void dispatch( Message message, Consumer<Message> consumer ) { ZonedDateTime dateTime = ZonedDateTime.now(); String strDateTime = dateTime.format( DateTimeFormatter.ISO_ZONED_DATE_TIME ); message.setDateTimeUTC( strDateTime ); message.setEncoding( "utf-16" ); message.setAssembledBy( ConsumerDemo.class.getName() ); byte[] contentBytes = message.getContent().getBytes(); CRC32 crc = new CRC32(); crc.update( contentBytes ); message.setChecksumAlgo( "crc32" ); message.setChecksum( Long.toString( crc.getValue() ) ); consumer.accept( message ); } |

⏹ Functional Interfaces and Testing

Examples in the discussion below refer to the following classes.

Functional Interface Demo Code

class GeoModel

An instance of this class

encapsulates a model of a rectangular area.

The model typically evolves over time

but it can be temporarly frozen,

during which time it doesn’t change.

It has many methods to get and set properties,

among them:

-

public double force( Point point )

public double stress( Point point )

public double velocity( Point point )

public double acceleration( Point point )

Returns the value of the named property at the given point.

-

public double force()

public double stress()

public double velocity()

public double acceleration()

Returns the value of the named property averaged over all points.

-

public void setForce( Point point )

public void setStress( Point point )

public void setVelocity( Point point )

public void setAcceleration( Point point )

Sets the value of the named property at the given point.

Important:

- For the purpose of testing, the model must be frozen before attempting to get or set a property.

- For the purpose of testing, a frozen model must not be frozen a second time.

- For the purpose of testing, an unfrozen model must not be unfrozen a second time.

class ModelMonitor

This class is used during testing only.

It maintains a GeoModel as an instance variable:

private GeoModel model;

and ensures that the model is accessed correctly.

For example,

each getter and setter in the model

is reflected by a corresponding getter/setter

in the ModelMonitor.

When the unit test class needs to get the velocity

of the model at a given point,

it calls geVelocity(Point) in the monitor;

the monitor makes sure that the model is frozen

prior to getting the property from the model,

and, if necessary, restores the state of model

after the operation completes.

The test class for the GeoModel class described above must make many calls to the class’s setters and getters. The brief description for GeoModel lists twelve setters and getters, and implies that there may be many more. Every access of a GeoModel object must be cast in the following logic:

- Save the frozen state of the model.

- If the model is not frozen, freeze it.

- Execute the access logic.

- Restore the frozen state of the model to the saved value.

To free the unit test programmer from having to write code to implement the above with every call to a setter or getter, the complementary class ModelMonitor has a setter and getter to encapsulate every setter and getter in the GeoModel class. Now, when the tester wishes to get, for example, the stress property, it calls the getStress method in the monitor class: double stress = monitor.getStress();

The getStress method in the monitor will then consist of code functionally equivalent to this:

public double getStress( Point point )

{

boolean isFrozen = model.isFrozen();

if ( !isFrozen )

{

model.setFrozen( true );

}

double stress = model.stress( point );

if ( !isFrozen )

model.setFrozen( false );

return stress;

}Rather than have to implement the above logic directly in every setter and getter, ModelMonitor can use functional interfaces in one or two helper methods to encapsulate the logic, for example:

private double

getDouble( Point point, Function<Point,Double> getter )

{

double rval = 0;

boolean isFrozen = model.isFrozen();

if ( !isFrozen )

{

model.setFrozen( true );

}

rval = getter.apply( point );

if ( !isFrozen )

model.setFrozen( false );

return rval;

}Now, getStress and all the other getters and setters can be reduced to something like this:

public double getStress( Point point )

{

double stress =

getDouble( point, p -> model.stress( p ) );

return stress;

}Default and Static Interface Methods

Before JDK 8, interfaces were not permitted to have executable code. As of JDK 8, they can implement methods; however, such methods must be declared static or default. The difference is:

- Default methods may be overridden by implementing classes.

- Static methods may not be overridden by implementing classes.

Default and static methods are always public. Many Java interfaces, including functional interfaces, now have default and static methods. One example is Consumer.andThen. Refer to the following sample program.

Note: the return value of andThen is type Consumer<T>.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 | public class ConsumerAndThenDemo1 { public static void main( String[] args ) { Consumer<String> toHomeOffice = m -> sendTo( m, "Home Office" ); Consumer<String> toNewYork = m -> sendTo( m, "New York" ); Consumer<String> toOmaha = m -> sendTo( m, "Omaha" ); Consumer<String> sendAll = toHomeOffice.andThen( toNewYork ).andThen( toOmaha ); // The following method invocation will send a message to the home office, // and then to the New York office and then to the Omaha office. sendTo( "Hello from New Guinea", sendAll ); } private static void sendTo( String message, Consumer<String> consumer ) { consumer.accept( message ); } private static void sendTo( String message, String recipient ) { // whatever processing is required to // send the message to the recipient } } |

In the above example, the accept at line 18 invokes sendTo(message, “Home Office”), sendTo(message, “New York”), and sendTo(message, “Omaha”).

Here’s an example that uses the default Predicate.or(Predicate<T>) method to search a list of ShowDogs for the first element that is less than six or is a Collie.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | public class PredicateDefaultMethodDemo1 { private static final List<ShowDog> showDogs = getList(); public static void main(String[] args) { showDogs.forEach( System.out::println ); System.out.println( "****************" ); Predicate<ShowDog> lessThan = d -> d.getAge() < 6; Predicate<ShowDog> breedEquals = d -> d.getBreed().equals( "Collie" ); // Get the first ShowDog that is less than 6, // or which is a Collie. ShowDog showDog = getShowDog( lessThan.or( breedEquals ) ); System.out.println( showDog ); } private static ShowDog getShowDog( Predicate<ShowDog> tester ) { for ( ShowDog showDog : showDogs ) if ( tester.test( showDog ) ) return showDog; return null; } |

Here’s another ShowDog example, using the static Predicate.not(Predicate<T>) method. The following logic selects a ShowDog that is not a Collie: // From public class PredicateStaticMethodDemo2 ShowDog showDog = getShowDog(

Predicate.not( d -> d.getBreed().equals( "Collie" ) )

);

Methods Returning a Functional Interface

A method can return a functional interface. In the following example, lessThanAge and breedEquals are methods that return a Predicate<ShowDog>. The main method obtains one of each Predicate and then composes a compound Predicate, which is passed to a method that searches for a ShowDog that satisfies both criteria.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | public class ReturnFunctionalInterfaceDemo { private static final List<ShowDog> showDogs = getList(); public static void main(String[] args) { showDogs.forEach( System.out::println ); System.out.println( "****************" ); Predicate<ShowDog> lessThan = ageLessThan( 6 ); Predicate<ShowDog> breedEquals = breedEquals( "collie" ); ShowDog showDog = getShowDog( lessThan.or( breedEquals ) ); System.out.println( showDog ); } private static Predicate<ShowDog> ageLessThan( int age ) { Predicate<ShowDog> pred = d -> d.getAge() < age; return pred; } private static Predicate<ShowDog> breedEquals( String breed ) { Predicate<ShowDog> pred = d -> d.getBreed().equals( breed ); return pred; } private static ShowDog getShowDog( Predicate<ShowDog> tester ) { for ( ShowDog showDog : showDogs ) if ( tester.test( showDog ) ) return showDog; return null; } // ... } |

The Optional Class

Before we go on to the next major topic, let’s briefly introduce the Optional<T> class. An Optional object encapsulates a non-null value of type T, which may or may not be present. This is useful in several contexts, including avoiding null pointer exceptions and working with multi-threaded logic in which a value needed by one thread is asynchronously calculated by another. Several of Java’s functional interfaces have methods that return Optional objects.

An Optional object may be empty or non-empty. If an Optional is non-empty, we say that a value is present in the object. If an Optional is empty, we say that a value is absent from or not present in the object. You cannot change the state of an Optional; if an Optional is empty, you can not “set” a value in it; if a value is present in an Optional, it cannot be changed to a different value.

Note: if I start with a variable pointing to an empty Optional, I can assign the variable a new, non-empty Optional. This is not the same as changing the original object’s state; it is creating a new object and changing the variable to reference the new object.

The primary operations you can perform with the Optional class include:

- Optional.empty(): Create an empty Optional.

- Optional.of(T value): Create a non-empty Optional<T> containing value.

- Optional.get(): get the value of the Optional if it is non-empty; if the Optional is empty, the get method will throw a NoSuchElementException.

- isPresent(): returns true if an Optional is non-empty

- orElse( T value ): if an Optional is non-empty, returns the value present in the Optional, otherwise returns value

Here is a simple example of using an Optional object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 | public class OptionalDemo1 { private static final List<ShowDog> showDogs = getList(); public static void main(String[] args) { showDogs.forEach( System.out::println ); System.out.println( "****************" ); Predicate<ShowDog> lessThan = d -> d.getAge() < 6; Predicate<ShowDog> breedEquals = d -> d.getBreed().equals( "Collie" ); // Get the first ShowDog that is less than 6, // or which is a Collie. Optional<ShowDog> showDogOpt = getShowDog( lessThan.or( breedEquals ) ); if ( showDogOpt.isEmpty() ) System.out.println( "no suitable ShowDog found" ); else System.out.println( showDogOpt.get() ); } private static Optional<ShowDog> getShowDog( Predicate<ShowDog> tester ) { Optional<ShowDog> firstShowDog = Optional.empty(); for ( ShowDog showDog : showDogs ) if ( tester.test( showDog ) ) { firstShowDog = Optional.of( showDog ); break; } return firstShowDog; } // ... } |

Streams

In this context, a stream is a sequence of elements of the same type. Streams are encapsulated in objects of type Stream<T>, where T is the type of an element in the stream. A stream may consist of 0 elements (the empty stream), n elements, or be effectively infinite in length. Examples of streams include:

- The sequence of prime numbers (type Stream<Integer>, of effectively infinite length).

- The sequence of lines in an empty text file (type Stream<String>, 0 in length).

- The sequence of elements in a List<ShowDog> object (type Stream<ShowDog>, of length n, where n is the number of elements in the list).

There are several ways to produce a stream, including:

- Using the Stream.of( T… values) method, which produces a stream of type T consisting of the sequential elements of the values array, for example:

Stream.of( "Mercury", "Venus", "Earth", "Mars" ) - Using Stream.generate( Supplier<T> supplier ) method, which generates an infinite stream of elements of type T:

// Generates an infinite stream of doubles

Stream.generate( () -> Math.random() )

// The following two examples are equivalent;

// they produce an infinite stream of ShowDogs

Stream.generate( ShowDog::new )

Stream.generate( () -> new ShowDog() ) - Using the List.stream() method, which produces a Stream<T> of all the elements in a list, for example:

List<ShowDog> showDogs = ShowDogGenerator.getShowDogs( 10 );

showDogs.stream()... - Using the method IntStream.range( int start, int end ), which produces a Stream<Integer> stream of the sequential integers from start (inclusive) to end (exclusive):

IntStream.range( 1, 11 ) - Many other examples, including:

- LongStream.range(long start, long end)

- IntStream.iterate(int seed, IntPredicate hasNext, IntUnaryOperator next)

- IntStream.iterate(int seed, IntUnaryOperator oper)

- DoubleStream.iterate(double seed, DoublePredicate hasNext, DoubleUnaryOperator next)

- DoubleStream.iterate(double seed, DoubleUnaryOperator oper)

Streams can be operated on, one element at a time, using methods from the Stream class. One example is the forEach( Consumer<T> action ) method, which applies the functional interface action to each stream element. Here’s an example that prints the squares of the integers in the range 1 (inclusive) to 11 (exclusive).

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | public class IntStreamToSquaresDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { IntStream.range( 1, 11 ) .forEach( i -> System.out.println( i + " -> " + i * i ) ); } } |

Some stream operations produce a stream, allowing them to be chained or pipelined together. The Stream.filter(Predicate<T> predicate) method: Stream<T> filter( Predicate<T> pred )

ignores elements of a stream that fail to satisfy pred. The output of the filter method is a stream consisting of the elements of the original stream that satisfy the predicate. This example traverses a list of ShowDogs and prints only those that are older than five years.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | public class StreamFilterShowDogsDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { List<ShowDog> showDogs = ShowDogGenerator.getShowDogs( 10 ); showDogs.stream() .filter( d -> d.getAge() > 5 ) .forEach( System.out::println ); } } |

This example prints the squares of just the odd numbers between 1 and 11.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 | public class IntStreamToSquaresDemo2 { public static void main(String[] args) { IntStream.range( 1, 11 ) .filter( i -> i % 2 != 0 ) .forEach( i -> System.out.println( i + " -> " + i * i ) ); } } |

Stream operations come in two flavors: intermediate operations that produce new streams and terminal operations that do not (thereby terminating the pipeline). Some of these operations are listed below; for a complete list, see the Stream class Javadoc.

Intermediate Operations

Some of the intermediate operations are:

- Stream.distinct(): produces a stream of unique elements (duplicate elements are filtered out).

- Stream.limit(long count): produces a stream of at most count elements.

- Stream.map( Function<T, R> mapper ): consumes an element of a stream and produces a new stream, possibly of a different type. See also: mapToInt(Function<T> map), mapToDouble(Function<T> map), and mapToLong(Function<T> map).

- Stream.flatMap( Function<T,R> map ): sometimes the element of a Stream is itself a Stream. The flatMap consumes an element of such a stream, producing a new stream consisting of the elements of the consumed element. See also: flatMapToInt(Function<T> map), flatMapToDouble(Function<T> map), and flatMapToLong(Function<T> map).

- Stream.skip( long count ): produces a stream of elements not including the first count elements of the original stream; the stream may be shorter than count, in which case an empty stream is produced.

- Stream.sorted(): returns the elements of the original stream sorted according to their “natural” ordering.

- Stream.sorted( Comparator<T> comp): returns the elements of the original stream sorted according to the order imposed by a Comparator.

- Stream.peek( Consumer<T> action): executes action for each element of a stream, returning the original stream as a result.

Terminal Operations

Some of the terminal operations are:

- Stream.allMatch( Predicate<T> pred ): returns a Boolean value indicating whether or not all elements in a stream satisfy a given Predicate.

- Stream.anyMatch( Predicate<T> pred ): returns a Boolean value indicating whether or not any element in a stream satisfies a given Predicate.

- Stream.noneMatch( Predicate<T> pred ): returns true if no elements of a stream satisfy a given Predicate.

- Stream.findAny(): returns an Optional containing some element of a stream; if the stream is empty, it returns an empty Optional.

- Stream.findFirst(): returns an Optional containing the first element of a stream; if the stream is empty, it returns an empty Optional.

- Stream.forEach( Consumer<T> action): Executes the given action on every element of a stream.

- Stream.toArray(): returns an Object array containing every element of the stream.

- Stream.collect(Collector<T,A,R> collector ): returns a Collection (typically from the Java Collections Framework) containing the elements of a stream. (Note: it would be unusual for you to implement a Collector yourself; you are far more likely to use a ready-made Collector from the Collectors class. See below for examples.)

- Stream.toList(): returns an unmodifiable list containing every element of the stream. (This method is not present in JDK releases before Java 16.)

Examples

The code for the following examples can be found in the project sandbox.

● Pipeline (1)

This example is based on the ReturnFunctionalInterfaceDemo program shown above. In the revised example, the for loop in the getShowDog method has been replaced with a pipeline.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 | public class ReturnFunctionalInterfaceDemo2 { private static final List<ShowDog> showDogs = ShowDogGenerator.getShowDogs( 10 ); // ... private static ShowDog getShowDog( Predicate<ShowDog> tester ) { // Remember findFirst returns a possibly empty Optional... // ... if you call get on an empty Optional it will throw an exception // ... instead use orElse, which handles the empty Optional. ShowDog showDog = showDogs.stream().filter( tester ).findFirst().orElse( null ); return showDog; } } |

● Collect (1)

Following is an example of using the collect operation. The Collector<T,A,R> implementation is provided by the Collectors class. The implementation chosen creates a List<> object (specifically an ArrayList<>).

Note 1: Remember that map is an intermediate operation, so its output must be a stream. The type of its argument is Function<T,R>, so the value returned by the function will be type R. There are several methods in the ShowDog class with names starting with put (putName, putBreed, etc.). These methods change the value of a property, just like their corresponding setters, and then they return this: public ShowDog putAge(int age)That makes the output of the map operation in the following example type Stream<ShowDog>.

{

this.age = age;

return this;

}

Note 2: to generate a random number between minNum and maxNum:

-

- Compute the length of the range: diff = maxNum – minNum

- Obtain a random number between 0 and diff: num = randy.nextInt(diff)

- Add the lower bound of the range: num += minNum

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 | public class ShowDogGenerator { /** List of show dog names to be chosen at random. */ private static final String names[] = { "fido", "spot", "sky", "miracle", "bozo", "browie", "blackie", "foxy", "wolf", "bowser", "bruiser", "noisy", "killer", "remedy", "rarebit", "prince", "king", "princess", "queenie", "sorceress", "slumber" }; /** List of show dog breeds to be chosen at random. */ private static final String breeds[] = { "terrier", "bloodhound", "sheepdog", "dachsund", "pointer", "collie", "setter", "doberman", "spaniel", "poodle" }; /** Minimum, randomly generated age of a show dog. */ private static final int minAge = 1; /** Maximum, randomly generated age of a show dog. */ private static final int maxAge = 10; /** * The maximum owner ID. * An owner ID between 1 and maxOwnerID, * inclusive, * is generated for each show dog. */ private static final int maxOwnerID = 5000; /** * Gets a list of randomly generated ShowDogs. * * @param maxCount the number of ShowDogs to generate * * @return a list of randomly generated ShowDogs */ public static List<ShowDog> getShowDogs( int maxCount ) { final int numNames = names.length; final int numBreeds = breeds.length; final int ageRange = maxAge - minAge; final Random randy = new Random( 0 ); List<ShowDog> list = Stream.generate( ShowDog::new ) .limit( maxCount ) .peek( s -> s.putName( names[randy.nextInt( numNames )] ) ) .peek( s -> s.putBreed( breeds[randy.nextInt( numBreeds )] ) ) .peek( s -> s.putAge( randy.nextInt( ageRange ) + minAge ) ) .peek( s -> s.putOwnerID( randy.nextInt( maxOwnerID + 1 ) ) ) .collect( Collectors.toList() ); return list; } } |

A few notes about the above code:

- names is a list of ShowDog names

- breeds is a list of ShowDog breeds

- Line 72: use Stream.generate to generate a stream. Each element of the stream will be type ShowDog.

- Note that ShowDog::new is an example of the use of a constructor reference. It’s equivalent to () -> new ShowDog().

- Line 73: limit the length of the stream to maxCount elements

- Line 74: generate a random number between 0 and the length of the names array; use that element of the names array to set the name of the generated show dog

- Line 75: generate a random number between 0 and the length of the breeds array; use that element of the breeds array to set the breed of the generated show dog

- Line 76: generate a random number between minAge and maxAge; use that number to set the age of the generated show dog

- Line 77: generate a random number between 1 and maxOwnerID (inclusive); use that number to set the owner ID of the generated show dog

- Line 78: accumulate the elements of the stream produced at line 69 into a List of type ShowDog

● Collect (2)

Another example of using a Collector is shown in CollectorsExample1.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 | public class CollectorsExample1 { public static void main(String[] args) { List<Point2D> aboveXAxis = DoubleStream.iterate( -5, x -> x < 5, x -> x + .1 ) .mapToObj( CollectorsExample1::cubicFunk ) .filter( p -> p.getY() >= 0 ) .collect( Collectors.toList() ); aboveXAxis.stream() .map( CollectorsExample1::toString ) .forEach( System.out::println ); } private static Point2D cubicFunk( double xco ) { double yco = Math.pow( xco, 3 ) + 2 * Math.pow( xco, 2 ) - 1; Point2D point = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco ); return point; } private static String toString( Point2D point ) { String fmt = "(%5.2f,%5.2f)"; String output = String.format( fmt, point.getX(), point.getY() ); return output; } } |

The following section discusses the above program, beginning with the two helper methods.

- Line 16: cubicFunk is a method that conforms to the requirements of the abstract method in the DoubleFunction<Point2D> interface. Given an x value, it computes the corresponding y value in the mathematical function f(x) = x3 +2x2 – 1. The result is a Point2D object encapsulating the (x,y) coordinate.

- Line 23: toString is a method that conforms to the requirements of the abstract method in the Function<Point2D,String> interface. It converts a Point2D object into a String of the form (x,y).

- Line 6: The iterate method in the DoubleStream interface generates a stream of double values from -5,0 to 5.0 in increments of .1. The signature of this overload of the iterate method is:

iterate(

where seed is the first value in the stream, hasNext is a predicate that terminates the stream when false, and next is a functional interface that generates the next value based on the previous value. Note: this overload was introduced in Java SE 9; it is not available in Java SE 8.

double seed,

DoublePredicate hasNext,

DoubleUnaryOperator next

) - Line 7: The mapToObj method takes the values produced by the iterate operation and generates a stream of type Point2D. For an argument to this method we are using a method reference equivalent to d -> cubicFunk(d). Compare the use of the mapToObj method to the use of the map method used at line 39 in ShowDogGenerator. The stream we are using here is type DoubleStream, a refinement of Stream. The DoubleStream interface overrides the map method to return a stream of doubles, so it is inappropriate for use in producing a stream of Point2Ds. That’s why we use mapToObj instead.

- Line 8: The predicate eliminates from the stream any Point2D with a y value less than 0.

- Line 9: The collect terminal operation uses the Collectors class’s toList method to accumulate a list of type Point2D. A reference to the list is assigned to the aboveXAxis variable declared on line 5.

● Pipeline (2)

Here’s a more involved example that reads an initialization file to produce a Properties object. The initialization file consists of name/value pairs of the form name=value. It also has blank spaces, blank lines, and comments (lines beginning with “#”), for example:

...

#################################################

## General grid properties

#################################################

# Grid units (pixels-per-unit) property

gridUnit=65

#################################################

## Main window properties

#################################################

# Main window width property

mwWidth=500

# Main window height property

mwHeight=500

# Main window background color property

mwBgColor=0xE6E6E6

...The application in the following example must:

- Read each line of the file.

- Discard all blank lines and comments.

- Discard blank space at the beginning and end of every line containing name/value pairs.

- Divide the name/value pairs (name=value) into name and value components, and insert the result into a Properties object.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 | public class PropertiesFileParser { private final File inputPath; public PropertiesFileParser( String filePath ) { inputPath = new File( filePath ); } public Properties getProperties() { Properties properties = null; try ( FileReader fReader = new FileReader( inputPath ); BufferedReader bReader = new BufferedReader( fReader ); ) { properties = getProperties( bReader ); } catch ( IOException exc ) { exc.printStackTrace(); System.exit( 1 ); } return properties; } private Properties getProperties( BufferedReader bReader ) { Properties props = new Properties(); props.putAll( bReader.lines() .map( String::trim ) .filter( Predicate.not( String::isBlank ) ) .filter( Predicate.not( s -> s.startsWith( "#" ) ) ) .map( s -> s.split( "=" ) ) .filter( a -> a.length == 2 ) .map( a -> { a[0]=a[0].trim(); a[1]=a[1].trim(); return a; }) .collect( Collectors.toMap( a -> a[0], a -> a[1] ) ) ); return props; } } |

Here’s a brief discussion of the above code:

- Lines 5 – 8: constructor that establishes the location of the initialization file to parse.

- Lines 13 – 16: try-with-resources statement that opens the target file and associates a BufferedReader with it. Due to the nature of the try-with-resources statement, the file will be closed automatically when the try block exits.

- Line 18: invoke the helper method that performs the actual parsing.

- Lines 20 – 24: perform I/O error processing, if necessary.

- Line 25: return the generated Pro5erties file to the caller

- Lines 28 – 42: perform the actual parsing of the input file.

- Line 30: create the Properties object.

- Line 31: invoke the Properties.putAll method. The argument passed to this method is the value of the expression constituted by lines 32 – 39.

- Line 32: invoke the lines() method of the BufferedReader. This method produces a Stream of type String (Stream<String>) whose elements consist of the lines of text in the initialization file.

- Line 33: remove blank space from the front and back of each line in the stream.

- Line 34: discard all blank lines from the stream.

- Line 35: discard all comments from the stream.

- Line 36: “split” each name/value pair into an array containing the name in element 0 of the array and the value in element one.1

- Line 37: filter out any result from line 36 that is not a valid name/value pair.

- Lines 38 – 42: remove white space (if any) from the beginning and end of the name and value strings.

- Line 43: accumulate the stream produced at line 38 into a Map<String,String>.2

1Note: The split method in the String class takes as an argument a regular expression. As regular expressions go, the one we use in this example is about as simple as it gets. But, if you don’t know what a regular expression is, be careful before you try to use split in a different context; try, for example, splitting the string “a.b” into the two-element array {“a”,”b”}.

2Note: The toMap method of the Collectors class requires two arguments:

- A Function<T,K> which takes a value of type T as input, yielding a value of type K for use as the key to a Map entry. In our example, a -> a[0] is the function that provides the key; and

- A Function<T,V> which takes a value of type T as input, yielding a value of type V for use as a value to a Map entry. In our example, a -> a[1] is the function that provides the value.

Reduction Operations

A reduction operation is an operation that reduces a stream to a single value or object. We’ve already seen some examples of reduction operations:

.collectreduces a stream to a collection.findAnyreduces a stream to a single element of the stream.allMatchreduces a stream to a Boolean value

Other reduction operations available directly from the Stream interfaces include:

- Stream.count: counts the elements in a stream.

- Stream.toArray: places the elements of a stream in an array.

- DoubleStream.average: computes the average of the elements in a stream.

- DoubleStream.sum: computes the sum of the elements of a stream.

- DoubleStream.max: computes the maximum of the elements of a stream.

- DoubleStream.min: computes the minimum of the elements of a stream.

● Reduction Operation from the Stream Library

Here are some examples of miscellaneous reduction operations available directly from the Java library.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 | public class MiscReductionExamples { private static List<ShowDog> showDogs = ShowDogGenerator.getShowDogs( 25 ); public static void main(String[] args) { countDemo(); countDemo( d -> d.getBreed().equals( "collie" ) ); averageDemo(); maxDemo(); } /** * Demonstrates the use of the * <em>count</em> reduction operation. * Counts the elements in a stream. */ private static void countDemo() { long count = showDogs .stream() .count(); System.out.println( "there are " + count + " show dogs" ); } /** * Demonstrates the use of the * <em>count</em> reduction operation. * Counts the elements in a stream * that match a given predicate. * * @param pred the given predicate */ private static void countDemo( Predicate<ShowDog> pred ) { long count = showDogs .stream() .filter( pred ) .count(); String feedback = "there are " + count + " show dogs " + "matching the predicate"; System.out.println( feedback ); } /** * Demonstrates the use of the * <em>average</em> reduction operation. * Find the average age * of a ShowDog in the showDogs list. */ private static void averageDemo() { // Note: .average() returns an Optional double average = showDogs .stream() .mapToDouble( ShowDog::getAge ) .average() .orElse( 0 ); System.out.println( "the average age is: " + average ); } /** * Demonstrates the use of the * <em>average</em> reduction operation. * Find the oldest ShowDog in the showDogs list. */ private static void maxDemo() { // Note: .average() returns an Optional Optional<ShowDog> oldest = showDogs .stream() .max( (d1,d2) -> d1.getAge() - d2.getAge() ); String name = "none"; if ( oldest.isPresent() ) name = oldest.get().getName(); System.out.println( "the oldest show dog is " + name ); } } |

● The reduce Method

To create your own reduction operation use one of the Stream.reduce() overloads. In the following example, a function, f(x), is evaluated for a given range of values. The application finds the point (x, f(x)) for which f(x) is closest to 0. The argument to the reduce method is a BinaryOperator<Point2D> that determines which of two Point2D objects is closest to the desired result. Note that the value returned by the reduce method is type Optional<Point2D>.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 | public class ReduceDemo { public static void main(String[] args) { // Given a stream of points, (x, f(x)) find the point // where f(x) is closest to 0. Optional<Point2D> closestTo0 = DoubleStream.iterate( -5, x -> x < 5, x -> x + .1 ) .mapToObj( ReduceDemo::cubicFunk ) .reduce( (p1,p2) -> Math.abs( p1.getY() ) < Math.abs( p2.getY() ) ? p1 : p2 ); String str = "none"; if ( closestTo0.isPresent() ) str = toString( closestTo0.get() ); System.out.println( "closest to 0: " + str ); } private static Point2D cubicFunk( double xco ) { double yco = Math.pow( xco, 3 ) + 2 * Math.pow( xco, 2 ) - 1; Point2D point = new Point2D.Double( xco, yco ); return point; } private static String toString( Point2D point ) { String fmt = "(%5.2f,%5.2f)"; String output = String.format( fmt, point.getX(), point.getY() ); return output; } } |

● The flatMap method (1)

There is often confusion over the purpose of the flatMap method. Like the map method, flatMap produces a stream of elements, so what’s the difference? Let’s look at an example first. In the following example, we intend to process every element in a two-dimensional array of integers. Our approach is based on Java’s design strategy, which treats a two-dimensional array as an array of arrays. We will stream the array, producing a sequence of arrays, each of which can then be streamed. We will try using the map method first.

public class MapVsFlatmapDemo1

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

int[][] values =

{

{ 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 },

{ 100, 200, 300 },

{ -5, -10, -15, -20, -25, -30, -35 }

};

Arrays.stream( values )

.map ( a -> Arrays.stream( a ) )

.forEach( System.out::println );

}

}The output of the above program is:

java.util.stream.IntPipeline$Head@38af3868

java.util.stream.IntPipeline$Head@77459877

java.util.stream.IntPipeline$Head@5b2133b1

Which makes perfect sense, even if it’s not what we want. The first stream operation generates three objects, each of which is of type int[]. The map operation feeds each int[] to Arrays.stream, which produces a reference to a stream object. Then, the three references are printed out by the forEach operation.

The result of the above program is probably not what the programmer intended. Likely, the programmer expected the elements in each int[] stream to be processed individually, producing output similar to this: 10

20

30

40

50

100

...

-30

-35

As shown in MapVsFlatmapDemo2, shown below, we can achieve this result by using flatMap instead of map:

public class MapVsFlatmapDemo2

{

public static void main(String[] args)

{

int[][] values =

{

{ 10, 20, 30, 40, 50 },

{ 100, 200, 300 },

{ -5, -10, -15, -20, -25, -30, -35 }

};

Arrays.stream( values )

.flatMapToInt( a -> Arrays.stream( a ) )

.forEach( System.out:: println );

}

}● The flatMap method (2)

A common use of flatMap is to combine multiple collections into a single collection. This example processes several lists of names, “flattening” them into a single list, eliminating duplicates. The example below is the main method from the application MapVsFlatmapDemo3 in the project sandbox. The complete code is in the GitHub repository.

public static void main(String[] args)

{

// Given:: listA, listB, listC, and listD are type List<String>

List<String> finalList =

Stream.of( listA, listB, listC, listD )

.flatMap( l -> l.stream() )

.distinct()

.collect( Collectors.toList() );

finalList.forEach( System.out::println );

}Parallel Streams

We won’t spend much time on this topic, but I wanted to make you aware of it.